The UN General Assembly could not come at a more precarious time for Libya.

In the last month, more than 100 people have been killed as Libyan state-sanctioned militias clashed with rivals in the capital Tripoli. A tenuous ceasefire agreed on September 4 has repeatedly been broken, with at least 11 dead in large-scale clashes that broke out on Thursday. Meanwhile, ISIS are exploiting the chaos by launching attacks on state institutions.

Political progress has shuddered to a halt despite an array of international efforts to bring about elections. A UN-backed government barely holds sway in Tripoli and is propped up by powerful, corrupt militias. The east of the country is controlled by Libya’s most powerful force, the Libyan National Army, which refuses to acknowledge the Tripoli administration.

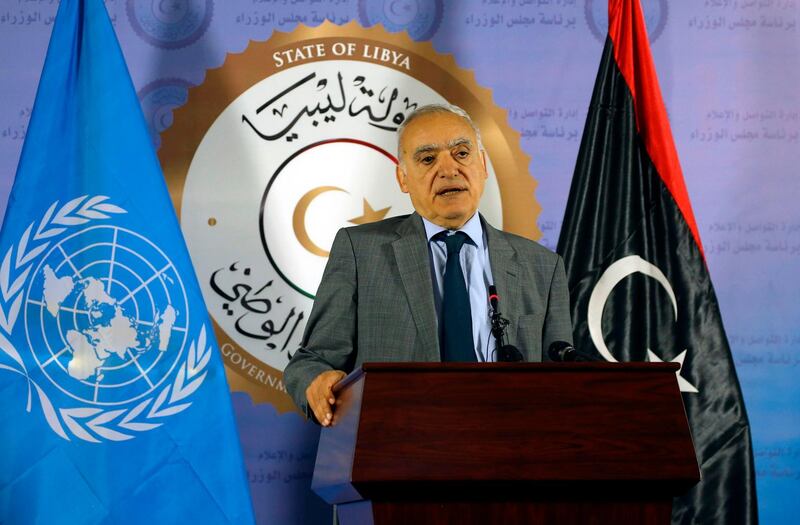

How much of this will be discussed, much less resolved, on the sidelines of the UNGA remains to be seen. The UN and its special envoy Ghassan Salame have previously tried and failed to unite the factions and bring about stability.

______________

Read more:

With Bashar Al Assad's survival seemingly assured, UN faces a different debate on Syria

UN postcard: reform remains critical for organisation to play effective peace-making role

UN to vote on final pact to manage refugee crisis

Donald Trump to support plan for 'Arab Nato'

______________

A separate peace effort was launched by French President Emmanuel Macron in May when he brought representatives from four of Libya’s largest factions together in Paris. They supposedly agreed to a December 10 election – but that deal already appears to have collapsed.

“The timing of the assembly is interesting. It is right when France must decide whether to take a step back from its initiative, which included having a constitutional basis for elections by September 16,” said Jalel Harchaoui, Libya expert at the University of Paris 8.

“Speaking to French officials, they say everything is fine and all is looking smooth. This is magical thinking. Will they stay like this or water down the rhetoric and try to see if a combination of efforts with countries such as Italy and the US can ensure a smooth transition.”

Hello from New York City. As the United Nations gears up for its 73rd General Assembly, Editor in Chief Mina Al-Oraibi previews the week ahead with producer Willy Lowry and why it matters to you. Follow our #UNGA coverage here: https://www.thenational.ae/world/united-nations

Posted by The National on Sunday, September 23, 2018

While the UN backed the French talks, another important player, Italy was angered by the intervention.

Italy accused France of pushing too hard for elections. France’s key role in the 2011 revolution that overthrew former dictator Muammar Qaddafi has been cited by Italy as a crucial reason for Libya’s instability and migration problem.

A Libyan politician who was present at the Paris summit said with goodwill from that meeting largely evaporated, UNGA could be crucial for resetting the agenda.

“I think the assembly will push for two things. The UN needs to make their mission Libya one of peace, not just ‘support’. They could also move to reform the presidency council and look to elections in 2019,” said the high-placed politician, who spoke on condition of anonymity.

Libya’s internationally recognised administration in Tripoli is led by a nine-man presidency council, though four members have suspended their participation. The unity government has also not been accepted by parliament and relies on corrupt, state-sanctioned militias to give it a semblance of security.

Threats to sanction the brigades or bring them under broader control have largely been empty. “The Tripoli cartel is supposed to be the protection of the presidency council, I would be surprised to see any of them being sanctioned,” said Karim Mezran, a North Africa expert at the Rafik Hariri Centre for the Middle East.

The breaking of the cease fire in #Tripoli demonstrates no one wields the stick in #Libya and therefore the conflict will worsen unless base facts are changed, such as a converging of strategy from the international community or a decision to actually help the country

— Karim Mezran (@MezranK) September 21, 2018

When Mr Salame took charge in June last year he was upbeat about being able to advance Libya’s stagnant political process. Following extensive meetings with politicians, military leaders, tribal figureheads and civilians, he unveiled his UN action plan in September 2017. The vision was based around a fair and inclusive process that could finally restore a united government, central bank, army and parliament.

Both the action plan and French-led election efforts appear to have failed, something that even Mr Salame has conceded – but that does not mean his ideas will not be discussed in New York said Mr Mezran.

“I imagine that the support to Mr Salame’s plan, especially a return to the first point of his action plan, will be central. That is how to move the political process without compromising the little equilibrium that exists,” he said.

“I think, and heard, that by returning to point one of the plan they mean the reduction of the presidency council to three members from the original nine and the appointment of an executive prime minister and cabinet to work with general support towards restoring a minimum of order and starting to rebuild the infrastructure,” Mr Mezran added.

However, a major stumbling block has always been Libya’s parliament. There are fears members could impede any reform.

“Time and time again, the House of Representatives has promised to produce referendum and election legislation. After three sessions dedicated to the referendum law, and numerous delays, the House of Representatives has failed to deliver this legislation. Those who have an interest in maintaining the status quo have spared no efforts to resist the needed change,” Mr Salame said recently.

The special envoy hinted at a change in tack when he said the chapter on the legislative process would close soon. “There are other ways to achieve peaceful political change,” he said.

“The reality is, if the UN really wanted to change up the presidency council, it could,” insisted the Libyan present at the Paris summit.

“I don’t think the HoR will be a limit in this, it will be overpassed by the UN,” said Mr Mezran.