With a song about love on the sound system, a big screen showing a French football match and generous servings of fresh papaya juice, the Harhara cafe seems like a good place to relax and escape the intensity of south Tel Aviv.

But its Eritrean clientele and staff are anything but tranquil. And for good reason. They are not wanted in Israel. If Prime Minister Benjamin Netanyahu's right-wing government has its way they will be among thousands of Eritreans and Sudanese given a difficult choice: indefinite prison time or deportation to Rwanda or Uganda where they would face an uncertain fate.

They bear harrowing stories of oppression, persecution and flight through Egypt's Sinai Peninsula. The plans to expel them seem harsh to many Israelis, whose forebears in many cases were themselves refugees. Many of the Eritreans fled open-ended military service in their home country.

Viewed as illegal work migrants and "infiltrators" by the government, expulsions were supposed to begin next month despite objections from groups including Holocaust survivors, doctors and airline pilots who said they would refuse to fly planes with deportees.

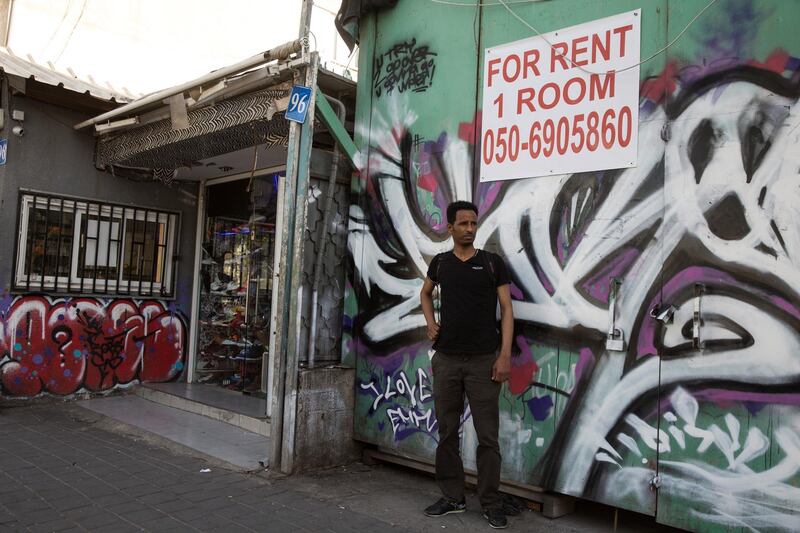

As part of deliberations on a petition by rights lawyers challenging the deportations, the country's supreme court last week temporarily froze the process. The legalities leave Eritreans such as Tesfum Goitom, 27, in nerve-wracking limbo, having heard horror stories from friends facing penury in Rwanda.

"I am really afraid," he said, his forearms showing burn marks from his job in a bakery in the nearby Israeli city of Holon.

"I am all the time worrying that they will expel me. I prefer going to prison here. That way I'll at least save my life."

The prospect of a journey to Rwanda rose on Monday with the visit of Avigdor Liberman, Israel's defence minister, to Kigali, as part of an African tour. As he met Paul Kagame, Rwanda's president, the government's plan came under increased fire at home.

People started to cross through Sinai into Israel in 2005, fleeing genocide, war and oppression in Sudan and escaping the tyrannical Eritrean regime, one of the world's leading human rights abusers. By 2012, there were more than 60,000 African asylum seekers in Israel but the construction of a border fence with Egypt that was completed in 2013 stopped the flow. None are currently entering the country. In recent years, 20,000 people accepted a return to Africa.

Although the Eritreans and Sudanese represent less than half of one percent of Israel's population, they have been depicted as a threat to the country's identity. In the cafe, customers are convinced the real problem is the colour of their skin, something Israeli officials deny.

"It's not everyone, but there are a lot of racists here," said Michael Avraham, 28.

While the tension is undoubted, the refugees have supporters.

_________________

Africans in Israel

Israel squeezes lifeline of Jerusalem’s Afro-Palestinians

A wave of African migrants flee Israel for a life of hardship and hope in South Sudan

Israeli detention centre for African migrants 'a prison'

Comment: Will the West copy Israel's refugee policy?

_________________

"We're told 36 times in the bible to take care of the stranger. That's absolutely a Jewish value," said Susan Silverman, a rabbi from the liberal reform stream of Judaism, who described the expulsion and imprisonment plan as both immoral and illegal.

The expulsion plan applies at first to 12,000 single men who do not have pending asylum claims. Interior Minister Arye Deri suggested during a Knesset committee meeting in late January that women, children and families would follow suit, meaning all 34,000 Eritreans and Sudanese would face expulsion or prison.

Shlomo Mor-Yosef, a senior interior ministry official, told the same committee that the deportations are a matter of state security.

"Just as there are soldiers on the border that safeguard the security of the country, our job is to guard the identity of the state of Israel in accordance with the policies of all of its governments throughout history. We are not sending anyone to their death. We are sending them to safe countries."

Such an opinion does not ring true to Mr Goitom, who recounted how he escaped in 2009 from the Sawa National Service Training Camp where 16 and 17-year-old school pupils in Eritrea begin their military service not knowing if or when it will end. Amnesty International's 2017/18 report on Eritrea makes reference to Sawa's "harsh conditions, military style discipline and weapons training."

"I was in the middle of school and everything changed. You don't know how long you are going to be in the army. It could be 40 years," Mr Goitom said.

When he got to Israel he was asked if he came for work. "I said no. "What I want is recognition as a refugee. I worked to eat."

That recognition is all but impossible in in Israel if you are Eritrean or Sudanese. Only 11 have been granted asylum over the last decade, compared to a more than ninety percent acceptance rate in Europe.

For Fiori Taklit, who works behind the cafe's counter, the thought of deportation is a constant companion.

"How can you sleep when all the time you are thinking about being expelled? If they throw me to Rwanda, what will I do?" she said.

The 25-year-old received no response at all to her application for asylum in 2013, she said, explaining that she left Eritrea because she was a Pentecostalist Christian. Adherence to that faith is banned there, suppressed and sometimes punished with extensive detention.

Like the other Eritreans interviewed, she had harrowing memories of crossing Sinai en route to Israel. "Three of our group died on the way. We didn't have food, water, anything. I paid $10,000 to the Bedouin to take me. Friends of my parents helped."

Daniel Avram, 26, recounted how Bedouin smugglers shot him in the leg three times when he was unable to meet their demand for $40,000.

His first year in Israel he could not work because of the injuries, but then he landed a job as a dishwasher. "Why to Rwanda?" he asked. "They can't even take care of their own people. How are they going to take care of refugees?"

Among Israelis in south Tel Aviv, where dilapidated stucco buildings in an area long neglected by the government abound, there is little sympathy for the Africans. Instead, blame is assigned with many saying they would be happy to see them leave, faulting them for crime. Israelis' prejudices are stoked by politicians in the ruling Likud party, including deputy foreign minister Tzipi Hotovely, who recently said the Africans are "terrorising" the area.

Taxi driver Gilad David said: "They have so many kids. In 20 years there will be at least a million of them. Can the state handle another million blacks?"

Dorin Dayan, who works in a sandwich shop, added: "They steal, they rape, they go around drunk at night and they hit each other. I only feel bad for the children, as for the rest, they should go."

But nearby, a grocer, who would give only his first name, Alex, an immigrant from the former Soviet Union, gave a different perspective: "They don't bother anyone. They are humans also. Colour is not important. It's the heart that counts."

Sigal Rozen, a staffer at the Hotline for Refugees and Migrants, an Israeli non-government organisation, believes mass deportations will not happen since most of the refugees would opt for jail.

Yet to Munya Abdullah, a young woman from nearby Jaffa, the problem lies in prejudice from a racist government.

"I'm an Arab so I know what it's all about. It's their skin colour and they're being taken out against their will."