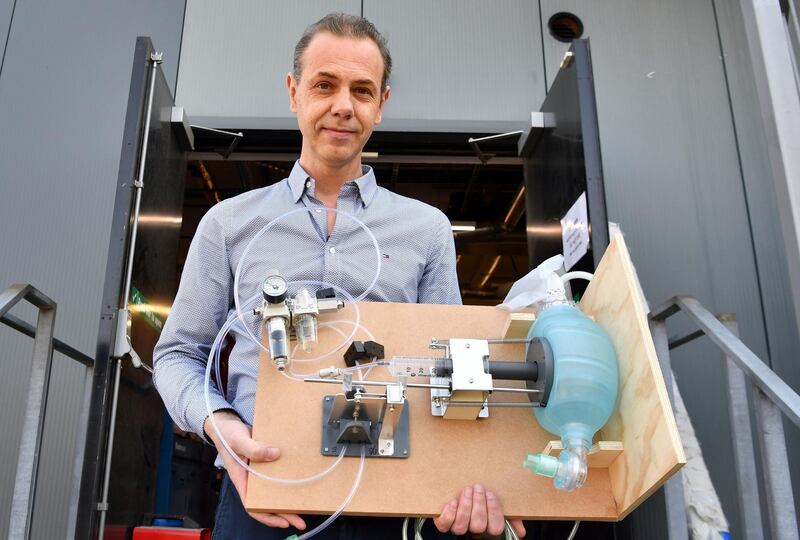

An expected surge in coronavirus patients needing hospital ventilators has triggered an avalanche of offers from British business to design, build and deliver working devices within weeks.

The increase in ventilator numbers is being touted as a panacea to the Covid-19 crisis when the peak in the number of infections hits the country imminently, but serious questions remain as to whether the target of 30,000 units can be met in time.

In an appeal for devices to the British manufacturing industry last week, the Secretary of State for Health, Matt Hancock, gave an open-ended pledge. “If you make it, we will buy it. No number is too high,” he said.

Among those to rally to the cause were big names such as Airbus, the Smiths Group and McLaren in proposed alliances with government that gave rise to comparisons of private factories churning out Spitfires in the Second World War. As yet, though, it has not produced the desired result in this peacetime crisis.

On Wednesday night, the household appliance firm Dyson announced that it had received an order from the UK government for 10,000 ventilators based on its CoVent prototype. The decision, however, has drawn widespread criticism on the grounds that Dyson, a name synonymous with innovative vacuum cleaners and fans, has no experience in ventilator manufacturing, and the new design cannot be put into production without approval from the Medicines and Healthcare Regulatory products Agency.

Before the announcement by the company’s billionaire founder, Sir James Dyson, the office of the Prime Minister, Boris Johnson, attempted on Tuesday to soothe concerns about the apparent lack of progress on actual procurement. “We have more than 8,000 ventilators on the front line currently, with more than 5,000 more expected to come online in the next few weeks,” a spokesman said.

Sightline with Tim Marshall - Europe under Coronavirus

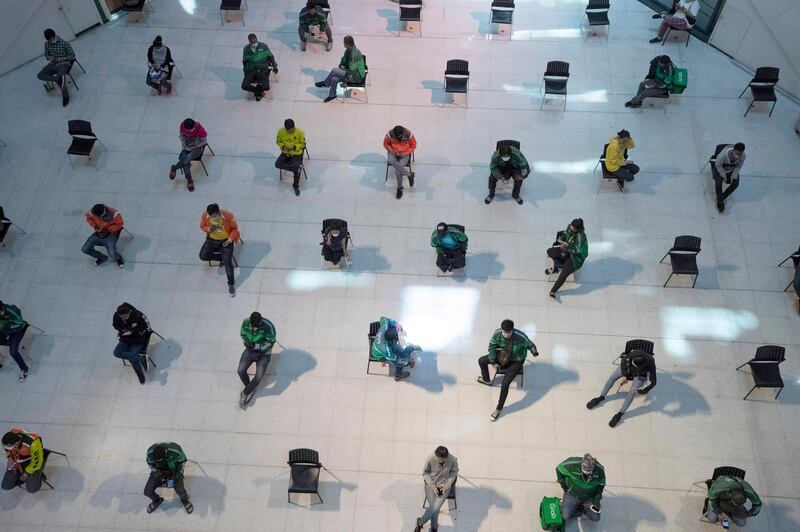

Some 8,328 people have been confirmed as having the virus in the UK and there have been 433 deaths. Barely a month ago, however, the number infected in Britain could be counted on one hand. As Professor Sir Mark Walport, the chief executive of UK Research and Innovation, conceded in comments to Sky News, "There isn't a country in the world that has the stocks of ventilators that are needed when you have a pandemic like this."

But even as governments faced criticism for reacting too slowly and many members of the public had not yet taken the spread of coronavirus from China seriously, citizens of the internet - or so-called netizens – had mobilised to fill the breach in medical supplies.

Among the community groups is Helpful Engineering, which describes itself as an open collective of volunteers seeking to apply unused engineering and manufacturing resources in innovative ways to fight the coronavirus. It has brought together thousands of people around the world via the Slack teamwork and collaboration channel, including scientists and doctors.

Read More

[ Latest updates on Covid-19 ]

[ Coronavirus: Migrants in UK detention centres confined to cells ]

[ Brought together in isolation: a letter from locked-down London ]

[ latest cases, deaths and recovery data for Middle East and rest of the world ]

A co-founder of the group, Dr Charles He, who has a PHD in Economics and an undergraduate degree in Life Sciences, says the platform is a more “agile” way of confronting the coronavirus problem than that offered by large corporations or fairly immobile governments.

“It was founded really as a way to help with Covid-19,” Dr He told The National, “but I guess a bigger purpose of being helpful in general. I just sat around for months along with other people watching as Covid sort of moved around the globe. It was very strange that governments wouldn’t react and so, like many other people, I made a group, a Slack group, to try to coordinate efforts.”

With such a coordinated, utilitarian approach, Helpful Engineering will achieve its goal to do the most good in the quickest time, he believes, and “many, many lives” can be saved.

Major engineering firms such as Rolls-Royce, Honda and Ford have confirmed that they have made contact with the UK government over fast-tracking the production of ventilators. However, both Honda and Ford confirmed to The National that there had been no developments in the days that had elapsed since then.

The Smiths Group is part of a consortium of companies working together in The Ventilator Challenge UK project. The technology company says that it is “significantly ramping up production” of its ParaPAC Plus ventilator - a compact, lightweight unit predominantly used while transporting patients - at its Luton site but has not revealed what the potential production capacity might be in the coming weeks.

The company’s CEO, Andrew Reynolds, said: “During this time of national and global crisis it is our duty to assist in the efforts being made to tackle this devastating pandemic, and I have been inspired by the hard work undertaken by our employees to achieve this aim.

Coronavirus: What is a pandemic?

“Alongside this, we are at the centre of the UK consortium working to set up further sites to materially increase the numbers available to the NHS and to other countries impacted by this crisis.”

Prodrive, a UK company that typically focuses on motorsport engineering, has also thrown its energies behind the national project. “At the moment, we have offered our support to the government to help make ventilators or any parts or systems that go into them, as we feel that it fits with the capabilities of a motorsport and advanced engineering business like ours,” Ben Sayer, a spokesman for Prodrive, told The National.

Another firm that has turned its innovative attention to the creation of medical ventilators is Gtech, which traditionally produces vacuum cleaners, e-bikes and gardening materials. The company’s CEO, Nick Grey, believes that Gtech can make around 100 machines a day within a week or two of having been contacted for help by the government’s Chief Commerical Officer, Gareth Rhys Williams, on March 15.

“At first I thought it was a hoax – being asked if I could assist in making up to 30,000 medical ventilators in as little as two weeks,” Mr Grey said. “When I realised that this was a genuine need, I felt compelled to help.”

The Gtech product is designed entirely from stock materials or those bought off the shelf but, underlining the hasty nature of the initiative, the firm also conceded that it needs help with some aspects of the process, such as steel fabrication, if it is to hit its 100-a-day output.

A smaller, more specialised company called Penlon, based in Oxfordshire, said it could feasibly double its output from the current 750 ventilators it makes a year, according to a report in the Financial Times, and has been named as a manufacturer that the government has asked to help support design efforts.

However, Craig Thompson, the head of products and marketing at Penlon, is among those within industry who have highlighted the difficulties associated with quickly manufacturing medical devices.

While the government has set out the minimum specifications needed for clinical use, there are still concerns over safety standards or the consequences of potential shortcuts. Mr Thompson warned that speedy turnarounds were unrealistic because of the heavy burden of standards and regulations that must be complied with. “Typically, a new medical device takes two or three years to develop and launch,” he told the BBC.

But Dr Marion Hersh, an expert in biomedical engineering at the University of Glasgow, told The National that the wide range of tests on initial prototypes and to ensure quality control once the ventilators were produced was crucial.

"They will include things like the working of the alarms and the performance of the devices - preferably tested on well people before they are tested on people with Covid-19 respiratory problems,” Dr Hersh said. “This is a human technology system, but the focus is on the technology. There has been some mention of the ventilator being intuitive to use and not needing more than half an hour training in the specs. However, this training needs to be organised,” she said.

"NHS staff are even more overworked and tired than normal. Operator error due to lack of training and familiarisation time can cause as many problems as a poor design.”