Half a century after the first man walked on the moon, Nasa has decided it’s time a woman did the same. And after a surprise hike in funding from President Donald Trump, the agency says it could happen within five years.

Nasa sees returning to the moon as vital to its plan to revive America’s moribund space programme by sending astronauts to Mars.

But decades of empty presidential promises, stop-start funding and technical challenges have cast doubt over Nasa’s ability to get astronauts to Earth orbit, let alone the Red Planet.

No US-built rocket has been put an astronaut in space since the Space Shuttle programme ended in 2011. Instead, it pays about $75 million per trip to hitch a ride aboard Russia’s 1960s-vintage Soyuz spacecraft.

Now that may all change following a characteristically punchy tweet from President Trump earlier this month. It declared his intention to “return to Space in a BIG WAY!” – and came with an extra $1.8bn on top of the $21 billion budget request made by Nasa for its moon mission in 2024.

Within hours of the tweet, the space agency’s chief Jim Bridenstine had unveiled the name of the project and its goal: “Fifty years after Apollo, the Artemis programme will carry the next man and first woman to the moon”.

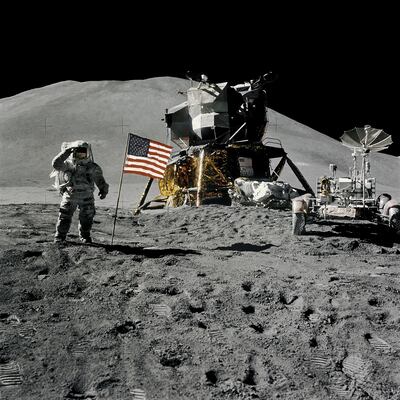

The name is fitting: Artemis was the Greek goddess of the moon and twin sister of Apollo. But almost half a century after Apollo 17 commander Gene Cernan stepped off the moon, why hasn’t a woman followed in his footsteps?

The obvious answer is that women aren’t robust enough for the rigours of spaceflight.

Obvious, but wrong.

Even at the dawn of the Space Race in the 1950s, studies were debunking the idea that the “weaker sex” weren’t up to taking part.

Studies by US Army physician Dr Randolph Lovelace and Jackie Cochran – the first female pilot to break the sound barrier – suggested that by typically being lighter and smaller, women also used less oxygen, food and fluids, making them potentially ideal astronauts.

By 1961, Dr Lovelace had bolstered the case by putting female pilots through the same notorious physical tests as male candidate astronauts. Of the 19 who took part, 13 passed. But as the tests were not part of the official Nasa programme, the women were barred from continuing their training.

Two decided to protest at what they saw as discrimination, and succeeded in getting their case heard by a special Congressional Subcommittee - two years before the 1964 Civil Rights Act brought such discrimination to national attention.

Their ground-breaking protest ended after Nasa pointed out that all astronauts also had to be qualified test pilots with engineering degrees – a combination no woman then possessed.

Not everyone was convinced by this, however, pointing out that Nasa bent the rules for John Glenn, the first American to orbit the Earth, who lacked an engineering degree.

In her study of the integration of female astronauts into Nasa’s programme, historian Dr Amy Foster of the University of Central Florida, argues the real barriers were “largely political and cultural”.

The power of political and cultural issues was highlighted in 1963 when the Soviet Union added the flight of the first female cosmonaut to its growing list of space-based triumphs.

In his new book Heroes of the Space Age, historian Rod Pyle credits Soviet Premier Nikita Khrushchev with the decision to recruit female cosmonauts to the official space programme.

According to Pyle, this had never been a serious consideration until Khrushchev realised the political capital to be gained from showing that women were – in theory at least – treated as the equals of men in the Soviet Union.

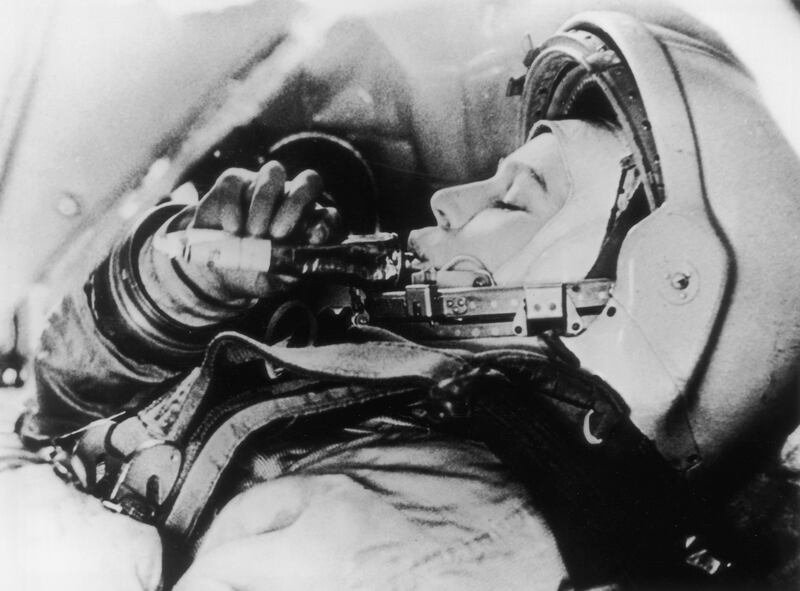

Four candidates were selected for training, with 26-year-old Valentina Tereshkova making her solo flight in Vostok 6 in June 1963.

It took another 20 years before Nasa matched the achievement, when 32-year old Sally Ride became the first American woman to go into space, aboard the Space Shuttle.

But since then, the number of female astronauts has soared. Of the 500-plus who have made Earth orbit so far, over 60 – around 1 in 8 - have been women. That’s more than double the proportion of female airline pilots world-wide.

They have also accomplished everything achieved by their male counterparts, from space-walks to being in command of the International Space Station.

Every achievement, that is, apart from one: walking on the moon.

There are no obvious reasons why a woman cannot eventually join the elite band of 12 men who stepped onto the lunar surface. But a mission to Mars may be a leap too far.

While the Apollo missions to the moon and back lasted no more than a fortnight, a round trip to Mars is likely to take at least 14 months.

During that time the crew will be exposed to radiation streaming through space from the sun. This is around 100 times the average yearly dose experienced on Earth – and there is concern that female astronauts may be especially vulnerable.

Research by Nasa suggests that because of their higher risk of breast, uterine and ovarian cancer, female astronauts should be exposed for only about half the time of their male counterparts.

This is already putting limits on how long women can stay aboard the International Space Station. It’s far from clear how that demand could be met on a mixed-crew mission to the Red Planet.

Protecting astronauts from space radiation is one of the biggest obstacles facing Nasa’s ultimate goal. Perhaps some technological breakthrough will be found to protect the first astronauts to Mars from the deadly threat.

But as things stand, while a woman may soon walk on the moon, the first person to walk on the Red Planet will most likely be a man.

Robert Matthews is Visiting Professor of Science at Aston University, Birmingham, UK