In the 2011 comedy-thriller The Guard, Brendan Gleeson, playing a jaded Irish cop, is drinking on duty, shooting bad guys in a pub videogame. An excited junior officer tells him that there's an FBI agent in town. "Drugs smuggling," Gleeson scoffs. "Either that or it's another sighting of Whitey Bulger at a museum."

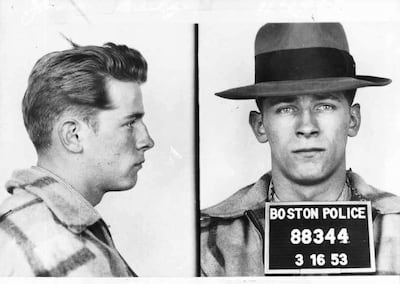

Well, no more. Irish-American mobster James Joseph "Whitey" Bulger, 89, was found choked and beaten to death inside Hazelton federal penitentiary in West Virginia last week. Bulger – serving two consecutive life sentences and a marked man for having "snitched" to the FBI – was killed hours after being transferred to the high-security prison. "He died the way he lived," a Boston Herald editorial read, describing Bulger's death as a "deserved end".

Bulger was no run-of-the-mill street hoodlum. The hardened Boston mobster had a hand in everything from drug dealing and money laundering to arms smuggling and extortion – his catch-me-if-you-can career received the Hollywood treatment not once, but twice, underscoring the big screen’s love for a bad guy.

In The Departed (2006), Jack Nicholson led an all-star cast, playing a Boston underworld boss based on Bulger. Johnny Depp also portrayed Bulger in 2015's Black Mass. That Bulger cropped up tangentially in The Guard – released weeks after he was finally arrested by the FBI – was doubly ironic given that Gleeson himself portrayed real-life Dublin gang boss Martin Cahill alongside Jon Voight in 1998's The General.

Between 2002 and 2011, unconfirmed sightings of Bulger in Ireland – as well as Uruguay, France, Italy, Canada and the UK – were common. The story of an on-the-run senior citizen with a history of visceral violence was catnip for moviemakers.

Gangster films are a Hollywood staple, up there with war movies and boxing flicks. The United States' love affair with true crime often increases a film’s chances of making a return on a studio's investment. However, many of cinema’s gang lords, real and fictional, are shown to have some sort of redeeming feature or moral core, perhaps to make them more palatable to moviegoers.

What's common in many of them is the "Robin Hood" aspect of their careers. Pablo Escobar, the Kray twins and Al Capone – all dispensed favours and supported the downtrodden – unless those communities, or members of them, stood up to the gangsters.

In 1992, Nicholson – who revelled in playing the bad guy – portrayed real-life union baron Jimmy Hoffa. Tainted by associations with the mob and convicted in 1964 of fraud, jury tampering and attempted bribery, Hoffa insisted everything he did was for the “working man”.

In Hoffa, Nicholson tells a roaring crowd: "We have led the Teamsters, and the Teamsters have led the American working man into the middle class, and, buddy, we intend to stay here."

In postwar London, the Krays – Ronnie and Reggie – controlled whole communities with the threat of violence. Their on-screen portrayals, in 1990 by Spandau Ballet's Gary and Martin Kemp and by Tom Hardy in 2015's Legend (the movie's title itself revealing a sneaking regard), also depicted these dangerous men as East End boys who loved their mum.

Many people remember Robert De Niro's turn as Al Capone in 1987's The Untouchables. Prowling around a black-tie dinner of subordinates, Capone extols the virtues of "teamwork" to his array of nodding dogs before murdering an underling with a baseball bat. But even Capone, linked to the Saint Valentine's Day Massacre of seven rivals in 1929, opened soup kitchens for hungry Chicagoans during the Great Depression in 1931.

This year's Loving Pablo, a biopic of Colombian crime boss Pablo Escobar starring Javier Bardem, was accused of rehashing tropes of the drug trafficker's life, particularly how he simultaneously ruled the streets of his base in Medellin. while also funding football teams, schools and parks in impoverished communities.

The movies give their fictional crime lords some sort of moral compass. Al Pacino's excruciatingly violent drug trafficker Tony Montana in 1983's Scarface balks at detonating a radio-controlled bomb under a journalist's car because there are women and children inside. Montana was a monster, but his image is plastered over posters and T-shirts across the world, representing someone who took from a world which gave him nothing.

But Bulger was irredeemable. Linked to 19 murders, he lacked this essential charisma for the truly memorable big-screen crime boss.

___________________

Read more:

[ Will Smith: 'Bad Boys 3' is 'official' ]

[ Aretha Franklin movie to finally premiere 46 years after filming ]

[ From Goldfinger to Scaramanga: 56 years of James Bond villains ]

___________________

Movies are accused of glamorising violence – and often they do. But fans of on-screen gangsters have selective memories. De Niro’s Capone bludgeons a man to death. Reggie Kray repeatedly stabs Jack “The Hat” McVitie at a party. Escobar’s hitmen shoot, stab and bomb thousands of Colombians. We know what these men did, but often choose to remember them as something else.

This will not be the last we hear of Whitey Bulger. Just a week after his death, a former Scotland Yard investigator claimed that artworks worth US$500,000 million stolen in a Boston heist in 1990 had been smuggled to Ireland, where Bulger had connections.

Someone, somewhere, is already writing that script.