Last week, Fikra Design Studio announced the region's first-ever Graphic Design Biennial, which will take place in November in Sharjah. It was headline news – but it is just one of a number of ambitious projects that Salem Al Qassimi, the founder of Fikra, has launched in the field of graphic design in the UAE.

“Graphic design” suggests a far narrower window than it should: Al Qassimi’s enquiry is as much about the potential of his chosen field as it is about the unique and changing context of the UAE.

It goes without saying that in the UAE, English is the lingua franca of business, despite the fact that most of the original residents are, and the inherited wealth of the country is, among Arabic speakers. The bilingual nature of the Emirates fascinated Al Qassimi from the very start of his career, when, upon returning to Sharjah after working in London design firms, he set up Fikra in 2006.

At the time it was the only graphic design studio in the UAE to put Arabic-language typography on a par with that of the English language. (“Fikra” means “idea” in Arabic.) He enlisted the help of calligrapher Wissam Shawkat (the two worked at the same branding agency in Dubai) to set up typefaces that could respond meaningfully to the concept of the publication or brand, and created messaging that reflected Arabic as well as Western cultures. Clients were typically those that straddled both cultures as well, such as the exhibition and studio space network Tashkeel or the Dubai fashion house Bouguessa.

“Arabic was becoming secondary, whether through branding work or communication, and that frustrated me,” he explains. “That’s why a lot of people came to us – not because they felt that the Arabic is more important than the English, but that the English isn’t more important than the Arabic. The two should work cohesively together, both in terms of the script and the cultures.”

In 2009, he took a punt and applied to only one graphic design school: RISD, the highly respected art and design school in Providence, Rhode Island. He was accepted and began a two-year master’s in graphic design, where he began to look at his native country from afar.

“When I went to RISD, the question was, ‘why do we always have to have bilingual identities?’,” he recalls. “I wrote a book about the hybrid mainstream identity of the UAE. I started to look at our identity through the lens of graphic design, landscape, dress. My design work became a window into the Emirati culture.”

When he returned to the Emirates, design seemed no longer a profession but a tool that could shed light on a new culture that was forming. He set up “Afkar Fikra” – the ideas of an idea: “a platform that was completely focused on self-directed, self-initiated projects that look into the culture of the UAE,” as he describes it. “That was the moment that it all started.”

Afkar Fikra used its expertise and its income from Fikra Design Studio to investigate Emirati identity and its intersection with design. A co-authored book looked at the cafeterias of the UAE, which serve a diverse clientele, and discovered a culture of surprisingly topical graphic design trends among them: one sugary sweet blue juice is called the Facebook, after its colour. Another, in green and white, is called the WhatsApp, and a yellow one called SnapChat.

One of the book’s co-authors, Alia Al Sabi, created spreads using the stock inventory of the design agencies that cater to the cafeterias, where you can buy a typeface, food pictures, and the layout of a menu at one go – a menu for menus. “You can set up a graphic design identity in 20 minutes,” says Al Qassimi, seeming half-impressed.

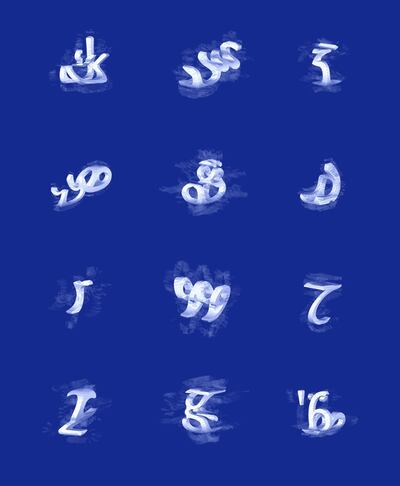

Other projects applied new technologies to Fikra’s inaugural subject, the bilingual nature of life in the UAE. “The UAE was becoming progressive and ultra-technological,” Al Qassimi says. “We wanted to explore that facet, while using it to look at the idea of hybrid forms. So we designed a 3D typeface that is interactive: from one perspective you see the Latin alphabet, and from the other you see Emirati Arabic. You move your hand, and the typeface keeps changing.”

By this point, the landscape of Arabic design typography – and design in the UAE – had changed. Al Qassimi began teaching Arabic-language typography and design at the American University of Sharjah, and design had now become a priority, with Dubai Design District launched in 2013 and Dubai Design Week in 2015.

Many of the design projects that have developed are particularly rooted in Arabic, and specifically Emirati, culture – the crossover area in which Fikra began – but with Afkar Fikra, Al Qassimi’s work was becoming more conceptual and research-driven. He moved away from design as a commercially-led enterprise, and towards it as a study of messaging, communication, and cultural codes.

This is the area where his last two projects have found him. Alongside his wife, Maryam Al Qassimi, also a graphic designer who joined Fikra in 2013, Al Qassimi launched Fikra Campus earlier this year, in the same building on the border of Sharjah and Dubai where Fikra’s offices have always been. Comprising a cafe, exhibition space and library, at its heart it is a suite of co-working spaces that bring people involved in creative pursuits together.

“The idea of the space is built on the notion of serendipity,” he says. “People bump into one another and things happen. We see that over and over again. Someone came from LA and ended up collaborating with one of our designers-in-residence.”

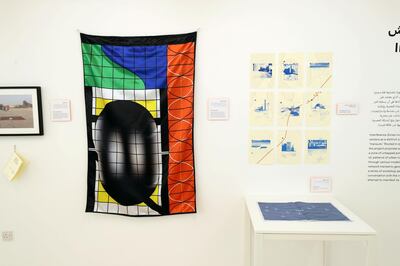

Two designers-in-residence stay in Sharjah for three months and, at the end of their stint, produce an exhibition for Fikra Campus. His designers this year, Adnan Arif from Sharjah and Kevin Zweerink from the United States, likewise chose to reflect on the idiosyncrasy of life in the UAE; Zweerink made, for example, a flag for the traffic-choked, low-lying residential area that populates the border between Sharjah and Dubai.

A regular series of talks called "Coffee with…" brings in people from different creative pursuits, and Fikra screen films on the building's rooftop, such as Jacques Tati's Playtime, with its famous cut-away view into a mid-century office building – a gridded glimpse that has long appealed to design aficionados.

With the Fikra Graphic Design Biennial, Al Qassimi will show international examples of expanded design to the UAE – and offer outsiders examples of what people are working on here. “Our work has three principles,” he says, “Knowledge, disruption and transformation.”

____________________

Read more:

The remarkable case of the missing MA Ibrahim: a long-lost painting resurfaces in an Abu Dhabi villa

Sultan Sooud Al Qassemi's mission to celebrate Sharjah's unsung architecture

Sharjah announces first Fikra Graphic Design Biennial

____________________